Pyro - A fast, small and documented Entity Component System

2018-10-30- Preface

- What makes Pyro special?

- API Overview

- Performance

- First impression of using an ECS

- Closing thoughts

Preface

This blog post expects that you are familiar with an Entity Component System, if you don't know what an Entity Component System is, then you should look at the RustConf 2018 Closing Keynote.

What makes Pyro special?

In contrast to many other ECS, iteration in Pyro is fully linear. Different combinations of components always live in the same storage.

// A Storage that contains `Pos`, `Vel`, `Health`.

(

[Pos1, Pos2, Pos3, .., PosN],

[Vel1, Vel2, Vel3, .., VelN],

[Health1, Health2, Health3, .., HealthN],

)

// A Storage that contains `Pos`, `Vel`.

(

[Pos1, Pos2, Pos3, .., PosM]

[Vel1, Vel2, Vel3, .., VelM]

)

For the given query

type PosVelQuery = (Write<Pos>, Read<Vel>);

// ^^^^^ ^^^^

// Mutable Immutable

world.matcher::<All<PosVelQuery>>().for_each(|(pos, vel)|{

pos += vel;

})

Pyro will find all the storages that contain a Pos and Vel component, create an position iterator from the position array of each storage and chain them together. The same is done for Vel. Under the hood it might look like this:

positions: [Pos1, Pos2, Pos3, .., PosN], [Pos1, Pos2, Pos3, .., PosM]

velocities: [Vel1, Vel2, Vel3, .., VelN], [Vel1, Vel2, Vel3, .., VelM]

^

Jump occurs here

The advantage is that iteration is always fully linear and no cache is wasted. The storage behind the scene is a SoA storage. This is very different from other ECS like specs where components live in the same storage that can be customized by the user.

API Overview

extern crate pyro;

use pyro::{ World, Entity, Read, Write, All, SoaStorage };

struct Position;

struct Velocity;

// By default creates a world backed by a [`SoaStorage`]

let mut world: World<SoaStorage> = World::new();

let add_pos_vel = (0..99).map(|_| (Position{}, Velocity{}));

// ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

// A tuple of (Position, Velocity),

// Note: Order does *not* matter

// Appends 99 entities with a Position and Velocity component.

world.append_components(add_pos_vel);

// Appends a single entity

world.append_components(Some((Position{}, Velocity{})));

// Requests a mutable borrow to Position, and an immutable borrow to Velocity.

// Common queries can be reused with a typedef like this but it is not necessary.

type PosVelQuery = (Write<Position>, Read<Velocity>);

// Retrieves all entities that have a Position and Velocity component as an iterator.

world.matcher::<All<PosVelQuery>>().for_each(|(pos, vel)|{

// ...

});

// The same query as above but also retrieves the entities and collects the entities into a

// `Vec<Entity>`.

let entities: Vec<Entity> =

world.matcher_with_entities::<All<PosVelQuery>>()

.filter_map(|(entity, (pos, vel))|{

Some(entity)

}).collect();

// Removes all the entities

world.remove_entities(entities);

let count = world.matcher::<All<PosVelQuery>>().count();

assert_eq!(count, 0);

Performance

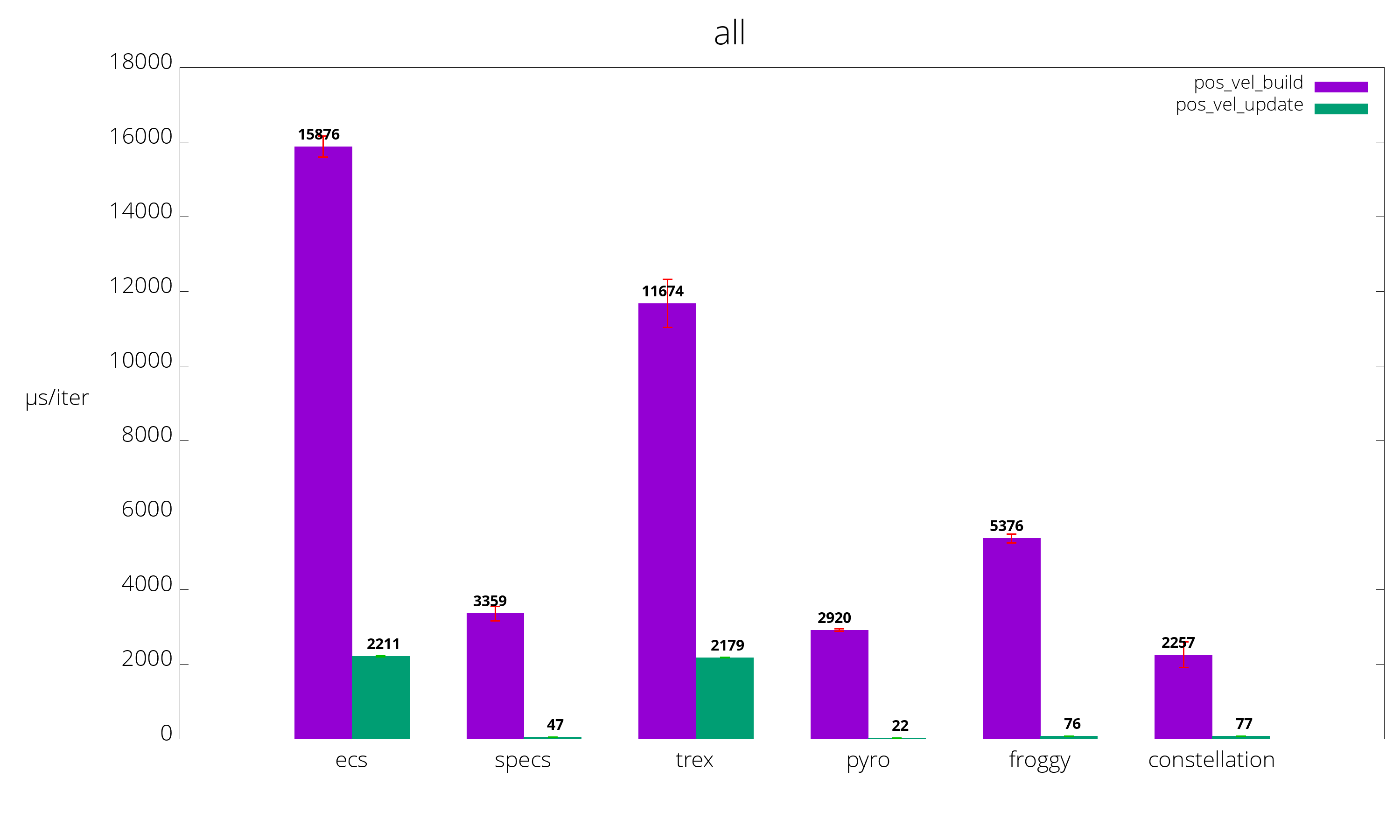

This is only the single threaded benchmark because I haven't implemented multi-threading yet for Pyro. It is not a fundamental problem, I just haven't found the time yet to implement multizip for rayon. The benchmark is also too simplistic to be useful, so take it with a grain of salt.

I am currently creating a more real world like benchmark, because I don't want to mindlessly optimize Pyro without any hard data. Although at the moment it is more of a personal playground than a benchmark.

First impression of using an ECS

Overall my impression is pretty good, but there are also a few downsides to an ECS.

Loose coupling:

pub fn kill_enemies(world: &mut World) {

let dead_enemies: Vec<_> = world

.matcher_with_entities::<All<(Read<Enemy>,)>>()

.filter_map(|(entity, (enemy,))| {

if enemy.health <= 0.0 {

Some(entity)

} else {

None

}

}).collect();

world.remove_entities(dead_enemies);

}

I think understanding local concerns is generally much simpler in an ECS because you only use what you need. For example in the example above we iterate over all enemies and filter out the enemies that have a negative health and then we delete those entities. There could be thousands of different enemy types, but that complexity is completely irrelevant for this function.

Seeing the big picture in an ECS might be much harder because we don't necessarily know which components a given entity has at run time. Compare this to something fromOOD

struct Player {

input: Input,

health: Health,

spells: Vec<Spell>

...

}

It is much easier to fully understand what a Player can actually do. Additionally it is easy to have incompatible components on an entity. An entity can have a position and velocity component, and then a function updates the position based on the velocity for every frame. Now there is also an Pathfinding component, which is used to navigate AI through the map. Having Position, Velocity and Pathfinding probably doesn't make much sense on the same entity.

Performance by default

While an ECS might not give you the best theoretical performance, it is still pretty efficient. All you need to worry about is "What data do I need, and how do I access it?". Also it makes certain runtime branches obsolete. For example imagine that you want to shoot a projectile. It should move along a line and explode when it collides with an enemy and apply damage. Now there can be many different projectiles. For example you might want a missile that spawns other missiles when it explodes. You could create an new enum

enum Missile {

Standard,

Spaw,

}

and then check at runtime which rocket you need to spawn.

You could also make your missile generic.

pub fn create_missile<Projectile: Component>(

asset: AssetId,

location: Position,

dir: na::Vector2<f32>,

speed: f32,

projectile: Projectile,

) -> Missile<Projectile> {

(

location,

Velocity(dir * speed),

Render {

asset,

scale: 1.0,

inital_rotation: PI / 2.0,

},

Orientation(0.0),

TimeToLive {

created: SystemTime::now(),

time_until_death: Duration::from_secs(3),

},

Flip::Right,

Damage(1.0),

projectile,

)

}

create_missile(AssetId::Missile, new_pos, dir, 700.0, SpawnMissile {})

create_missile(AssetId::Missile, new_pos, dir, 700.0, StandardMissile {})

So we can create two different missiles, and because they have one different component type, they will end up in two separate storages. Now we can abstract over those missiles at compile time, and we can skip the runtime branch.

#[derive(Copy, Clone)]

pub struct SpawnMissile;

pub struct SpawnMissileSystem {

spawn: Vec<Missile<StandardMissile>>,

}

impl OnProjectileHit for SpawnMissileSystem {

type Projectile = SpawnMissile;

fn on_projectile_hit(&mut self, pos: Position, _projectile: &Self::Projectile) {

let missiles = create_radial_missiles(pos, 150.0, 15.0, 12, StandardMissile {});

self.spawn.extend(missiles);

}

fn finish(&mut self, world: &mut World) {

let spawn = self.spawn.drain(0..);

world.append_components(spawn);

}

}

Of course you can do that without an ECS too but this is very natural in Pyro. Also Pyro follows the mantra 'If there is one, there are many.'. Everything that you do, you do in bulk. You don't spawn a single rocket, iterate to the next explosion and then spawn another rocket. You collect all the rockets that you want to spawn and then you spawn them in bulk. Right now this requires an allocation but the allocation can be avoided in the future with custom allocators.

Closing thoughts

I can't recommend it for any serious projects just yet. I only worked on it for under a week and there are some API deficiencies that I haven't addressed yet. I also haven't done much optimization and some parts of Pyro are implemented fairly slowly. If you want an ECS right now, you should use something like specs.

I mainly wrote this library for educational purposes. I had this idea on how to architecture an ECS for years but it is very hard to articulate it to other people. If you are interesting in knowing how an ECS might look under the hood, I encourage you to read the source code. It is ~700 loc right now and everything is documented. github, crates.io, documentation